My student years were moving along. The days were long and filled with learning. After the first year, during which I honed my basic nursing skills working in the hospital, I started my three-month clinical rotations in the specialties of Obstetrics, Pediatrics, the Operating Room, and Psychiatry. I was almost sure that I wanted to specialize in Pediatrics. Time will tell, I thought.

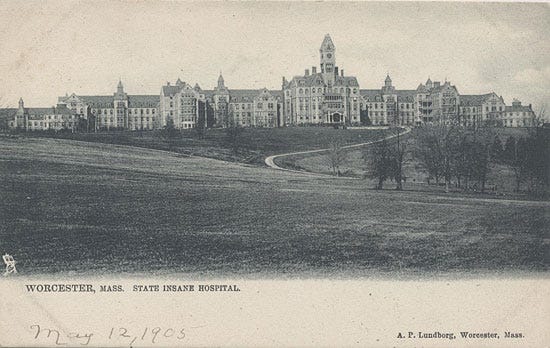

Psychiatry, my first rotation, was at Worcester State Hospital in November, December, and January of 1963/64. The hospital, built in 1833, was once known as the Worcester Lunatic Asylum. In the 1960s, the field of Psychology was evolving with the introduction of Freudian Psychology. However, Psychiatric care was the asylum model, which focused on custodial care and often neglected individualized treatment. Not much would change until the 1990s, when the deinstitutionalization movement began, leading to the closure of many large psychiatric institutions, including Worchester State Hospital. Freudian theories are still discussed and debated today.

As I write these introductions to my stories, I am becoming aware of how much my childhood experiences influenced my later decisions and career path. For example, when I was 8 years old my youngest brother, John, nicknamed “Jackie”, was placed at the Paul A. Dever Institution for the Mentally Retarded. He was 5 years old. I was told he was going away to school. I didn’t fully understand, until I was 12 what his disabilities were. We never lived together again. I am just now realizing how much our relationship as siblings affected the way I related to my patients, starting with Psych. (I will share John’s story next).

King Me

The drive down Asylum Avenue was bleak and dreary, as were the grounds of the Worchester State Hospital. I had just entered them and was looking for the students’ housing. All the buildings seemed like something out of a Victorian Horror Story. I hoped the student dorms would be the exception.

Winters in Massachusetts, especially in the Worcester area, were known to be severe. I dreaded this rotation and thought those were the worst three months to be in residence. I parked alongside the other cars and headed to what looked like the administration building to get further instructions.

I guessed I was in the right place as I joined a group of student nurses gathered in the foyer, all waiting to be told what to do next. Finally, a friendly person greeted us. He said he was there to escort us to our orientation room. “You students follow me”, he said. He was like the Pied Piper, and we followed him down three or four corridors before we came to a locked door at which he turned and ran away laughing loudly. That was how we learned that some patients were free to roam the grounds. We retraced the way we had come and met our true greeter who gave us a complete orientation and room assignments. She also made us aware that some patients who worked in the kitchen liked to spit in the food. I congratulated myself on bringing food and canned goods to stock in our kitchen. That was until I went to put them away.

The kitchen was in the basement down a long flight of stairs. I balanced my box of groceries and stopped at the top to switch on the light. As I looked down the stairs the floor seemed to turn from black to beige before my eyes. The floor appeared to be rolling into the wall. What was I seeing? I descended the stairs slowly all the while watching the floor change color. That’s when I realized what I saw were cockroaches retreating into the wall. I had to hold in my desire to scream. Oh my God could it get any worse? As the cafeteria was not a viable alternative, I learned to turn the light on for 5 minutes before going down the stairs. I would prepare my food quickly and take it back to my room. I spent as little time as possible in the kitchen.

The whole experience was crazy. The instructors included. They were always focused on Freudian theory (the belief that human behavior is driven by unconscious processes, many of which are related to sexuality and aggression). It seemed like they related most of the patients’ actions and conversations to something sexual. If a patient talked about a knife and wanted to stab somebody, they said it was his penis that he wanted to stick in someone. I was not convinced.

The student experience consisted of lectures on psychiatric illness, treatments, and medications. They told us about electrical shock therapy and ice baths, but I never saw any. We also had three sessions per week in a locked day room with the patients. Each session was followed by a post-clinical conference, where our interactions with the patients were discussed. The instructors always liked to explain what happened in Freudian terms. I thought a lot of what they said was garbage.

Most of the time I walked around the locked day room and smiled, trying to stay away from the patients who appeared highly agitated. Many of the patients were drugged and seemed out of it. I couldn’t see how they could say anything sensible while in that state, Freudian or otherwise.

One day, when I was in the men's day room, I noticed a middle-aged overweight man shuffling around the outer edges of the room. He was either fidgeting with his fingers or scratching his head constantly. I asked one of the attendants about him. He said his name was Ebbie; he did not speak and had been there since he was a very young boy. I was told he liked to play Checkers. So, after that whenever I was on duty I asked Ebbie to play Checkers, and we did. He never made eye contact or any sounds at all. He only focused on the Checkers, which he played well and beat me every time. I felt comfortable with him and liked doing something he seemed to enjoy. We played often.

On my last clinical day, we were still playing a round when the buzzer sounded for me to leave. Ebbie was about to win another game. Then, while he was still looking at the board, with his winning piece in his hand, he turned his head slightly towards me and said in a raspy whisper, “King me.” It was so unexpected and, at the same time, so profound that it brought tears to my eyes. I quickly said goodbye and left.

In the post-conference that day, I was told that no one knew he could speak. I felt conflicted. Proud that he chose me to speak to, but sad that he had been there so long with no one realizing he could speak.

I was just a student, but I vowed then that I would do something, sometime, somewhere to change practices where I encountered complacency in my profession.

Worcester State Hospital 1833 - 1991